Eye to eye with a 350-year old cow

Leeuwenhoek's specimens and original microscope reunited in historic photoshoot

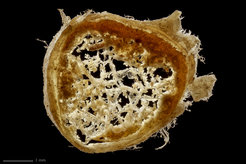

What may be the earliest surviving objects seen by microscope – specimens prepared and viewed by the early Dutch naturalist Antoni van Leeuwenhoek – have been reunited with one of his original microscopes for a state of the art photoshoot. This event allowed science historians to recapture the 'look' of seventeenth century science, recording the moment in digital films and with stunning high-resolution colour photographs for the first time.

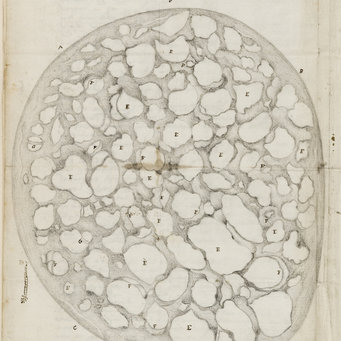

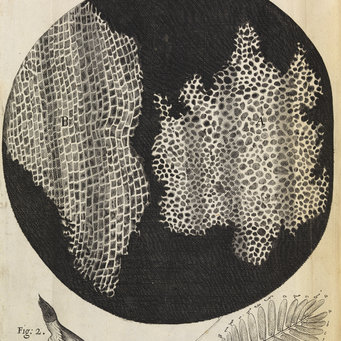

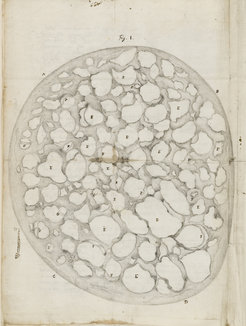

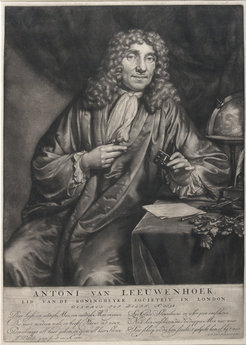

Delft-based naturalist Antoni van Leeuwenhoek was one of the first generation of serious microscope users, famous for his high-powered single-lens instrument that enabled him to see the natural world down to the scale of some large bacteria. As evidence for his 1670s and 1680s observations, narrated in letters to the London's Royal Society, he sent a variety of specimens: cows' optic nerves, sections of cork and elder, and 'dried phlegm from a barrel'.

In September 2019, these materials, in their original packages, flew back across the North Sea from the Royal Society to Leiden and the Rijksmuseum Boerhaave—the Dutch national museum of the history of science and medicine–where they were reunited with an original Leeuwenhoek microscope. The museum provided the opportunity for taking photographs through the original microscope, as well as the shooting of moving images.

Science and art historian Dr Sietske Fransen, former 'Making Visible' postdoc and now Leader of the Max Planck Research Group 'Visualizing Science in Media Revolutions' at the Bibliotheca Hertziana - Max Planck Institute for Art History orchestrated the event. She conducted readings of Leeuwenhoek's letters, while photographer Wim van Egmond and Rijksmuseum Boerhaave curator Tiemen Cocquyt were entrusted with the exceedingly delicate operation of filming through the priceless original silver microscope. In combining words and images, the team hope to arrive at a better understanding of Leeuwenhoek's groundbreaking observations and his use of artists to capture microscope views.

Professor Sachiko Kusukawa is the Principle Investigator of 'Making Visible', a four-year project based at the University of Cambridge dedicated to understanding the illustrative practices of the early Royal Society. She said of the photoshoot: "This event is a result of a network of scholars brought together by the 'Making Visible' project, an interdisciplinary research project supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council of the United Kingdom. It shows what can be achieved through true European collaboration, thanks to the Royal Society, Rijksmuseum Boerhaave, the University of Cambridge (CRASSH) and the Bibliotheca Hertziana – Max Planck Institute for Art History."

Amito Haarhuis, Director of the Rijksmuseum Boerhaave, commented: "With his microscopes Van Leeuwenhoek opened a whole new world, the microcosmos. He made it possible to see things that no human being had seen before. Thanks to this wonderful project and thanks to the latest technology, we are finally able to see in full detail what Van Leeuwenhoek might have seen 350 years ago. We couldn't be more excited!"

Keith Moore, the Royal Society's Librarian said: "Our first colour views of the sections cut by Leeuwenhoek's razor, with the lens made by the same hand, was a heart-stopping moment. The Royal Society will look forward to sharing the excitement with audiences in the run-up to the anniversary of this great Dutch scientist in 2023."

Note to Editors:

Background information

The specimens under the lens were:

- Cork sections and elder pith, 1 June 1674

- Optic nerves of cows, 4 December 1674

- Cotton seeds, dissected by Leeuwenhoek, 2 April 1686

- 'Heavenly paper' [algae mats/'dried phlegm in a barrel'], 17 October 1687

Although Leeuwenhoek's specimens have been imaged before, this is the first time that the latest digital techniques have been applied to the surviving specimens. Each item was recorded with still images before being filmed with a modern camera, through an original Leeuwenhoek microscope. These moving images allow researchers to replicate the changing light conditions and specimen orientation that were possible while using one of Leeuwenhoek's hand-held devices. It is the closest recreation to date of Leeuwenhoek’s working conditions.

Antoni van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723) was born in Delft, Netherlands, where he lived and worked. His interest in lens-making may have been spurred by his connection with the textile trade. He became adept at hand-crafting single lens microscopes. In these small instruments, the lens was held within silver or brass plates. Specimens were manipulated using an ingenious pin and screw arrangement: brought close to the eye they proved to be a powerful research tool. Very few Leeuwenhoek microscopes survive and today, they are among the treasures of Early Modern science in European museums.

Leeuwenhoek sent his many observations to the Royal Society in London, for publication in the journal Philosophical Transactions. Although the written descriptions were Leeuwenhoek's own, he collaborated with artists to capture what he was seeing in original drawings, which were engraved for wider dissemination. In a fifty-year period from the 1670s to the 1720s, Leeuwenhoek became the first, or one of the first, to see many aspects of life: he described 'animalcules' (micro-organisms such as rotifers), human and animal spermatozoa and investigated the structure of plants. Leeuwenhoek became a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1680.

Rijksmuseum Boerhaave is the national museum of the history of science and medicine in the Netherlands and one of the most important scientific and medical history collections in the world, home to four of the 11 remaining original Leeuwenhoek microscopes.

For more information on the story please contact:

Jesse Hawley

Assistant Press Officer

Jesse.hawley@royalsociety.org

+44 207 451 2508

For more information about Rijksmuseum Boerhaave please contact:

Anita Almasi

Marketing and Communications Advisor

anitaalmasi@rijksmuseumboerhaave.nl

+31 (0)71 751 9959

For more information about the University of Cambridge please contact:

Judith Weik

Communications Officer

jw571@cam.ac.uk

The Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) funds world-class, independent researchers in a wide range of subjects: history, archaeology, digital content, philosophy, languages, design, heritage, area studies, the creative and performing arts, and much more. This financial year the AHRC will spend approximately £98 million to fund research and postgraduate training, in collaboration with a number of partners. The quality and range of research supported by this investment of public funds not only provides social and cultural benefits and contributes to the economic success of the UK but also to the culture and welfare of societies around the globe.

Rijksmuseum Boerhaave is the Netherlands' national museum of the history of science and medicine. With a world famous collection spanning five centuries of research and innovation and based on close collaboration with prominent modern scientists, Rijksmuseum Boerhaave offers visitors of all ages a fascinating insight into the world of science. The museum is winner of the European Museum of the Year Award 2019. Rijksmuseum Boerhaave

Bibliotheca Hertziana – Max Planck Institute for Art History in Rome promotes scientific research in the field of Italian and global history of art and architecture. Established in 1913 as a private foundation by Henriette Hertz (1846–1913), today the Bibliotheca Hertziana is part of the German Max Planck Society and one of the world's most renowned research institutions for art history. Its impressive specialized library and vast photographic collection are an outstanding scientific resource for art historians from all over the world.

The Royal Society is a self-governing Fellowship of many of the world's most distinguished scientists drawn from all areas of science, engineering, and medicine. The Society’s fundamental purpose, as it has been since its foundation in 1660, is to recognise, promote, and support excellence in science and to encourage the development and use of science for the benefit of humanity. Royal Society's website, Twitter, Facebook.